♟️ How two amateurs beat the chess grandmasters

Two amateurs shocked the chess world by beating two grandmasters. Had they cheated? Did they receive help from Garry Kasparov? No, they had become centaurs. You can too. EXCERPT FROM MATHIAS SUNDIN'S NEW BOOK: THE CENTAUR'S EDGE

Share this story!

Excerpt from "The Centaur's Edge – How to Think, Write, and Communicate Better and Faster with ChatGPT". Out soon.

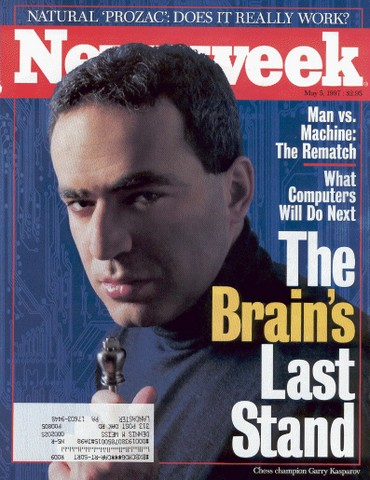

"The Brain's Last Stand" was the headline Newsweek used on its cover for the match between the grandmaster and world chess champion, Garry Kasparov, and IBM's chess computer, Deep Blue. Chess has been a representation of intelligence for centuries, and matches have determined who is the smartest, even between countries. One of the Cold War's bloodless battles occurred when Bobby Fischer played against Boris Spassky in Iceland in 1972, and the whole world watched. After the match, interest in chess reached record levels.

In the lead-up to Kasparov's match against IBM's $10 million computer, it was not West versus East. The year was 1997, and the Soviet Union no longer existed. Now it was man versus machine. Flesh against silicon. If the brain lost to the circuits, did that mean the end of the human era and the beginning of the machine era? And what would happen to chess? Kasparov faced severe criticism from other chess players for participating. Who would want to play chess if computers were better at it?

When the match started, Kasparov won the first game. Brain fans breathed a sigh of relief. They should not have, because Deep Blue won the second game. 1-1. The next three games ended in draws, and going into the final game, the score was tied, 2.5 to 2.5.

Interest around the world now reached the same levels as for Fischer against Spassky 25 years earlier.

In the decisive game, Kasparov played an opening known as "Caro-Kann", which has over a hundred years of history. A fairly common defense against it is to sacrifice a rook. Kasparov didn't think the computer would make such a move, as it has no apparent short-term benefit, quite the opposite. But that's exactly what the computer did, and Kasparov found himself at a disadvantage. Twenty moves later, he resigned and stormed angrily out of the room.

The brain had lost. Checkmate.

But the pessimists were wrong about what happened next. Instead, interest in chess increased. Even when you could have a chess computer on your mobile phone that was much better than Deep Blue, interest did not wane. On the contrary. The better the chess computers became, the more people wanted to play chess. Over the past three years, 100 million new players have started, just through chess.com. More players and better sparring partners in the form of computers have also made humans better players. In the 25 years after Fischer vs. Spassky, five people reached the super-grandmaster level, with over 2700 points in Elo rating. In the 25 years following Kasparov's loss to Deep Blue, 127 people have reached that level.

Kasparov is not known as a good loser, and this was no exception. He accused IBM of cheating and said humans must have helped the computer during the games. No one would have been surprised if Kasparov had become a doomsday prophet and started warning about the dangers of AI. He chose a different path.

Instead, he created a new form of chess, where humans play together with machines. The year after his loss, he hosted a tournament in León, Spain, where human players could use a PC with a chess program. He called it "Advanced Chess."

A few years later, something happened that amazed both Kasparov and the chess world. A 2005 tournament for advanced chess attracted both grandmasters and amateurs competing for a $10,000 first prize. The participants competed in teams where a human player could get help from both other people and computers. In the semifinals, three teams with grandmasters faced surprisingly a team of amateurs. No one believed that amateurs could make it to the semifinals against such qualified opponents. Even less to the final, but that's how it turned out.

In the finals they were up against the grandmaster Vladimir Dobrov with an Elo rating of over 2500, who teamed up with another grandmaster with an Elo rating over 2600. Elo rating is the chess world's way of measuring players' relative strength. The highest Elo rating ever achieved is by Magnus Carlsen with 2882. Kasparov is second with 2851. The two amateurs had 1685 and 1398, respectively. One can become a grandmaster with a rating of 2500 or more. The title of expert is reached at 2000. Below the expert level, players are divided into classes from A to F, where the F level includes beginners with an Elo of 750-1000.

The two amateurs were in class B and D. In other words, they were two hobby enthusiasts who played chess in their spare time, facing two of the world's best chess players. The amateurs had three ordinary personal computers and a handful of chess programs. Their opponents had powerful computers and access to the most advanced chess programs.

The outcome of the match should have been a foregone conclusion. But it wasn't. The amateurs won, shocking both Kasparov and the chess world. How did this happen? Speculations started immediately. Had they received help from Kasparov or some other elite player? No. The answer lay in how they used the computers.

The two amateurs, Steven Cramton and Zachary Stephen, were chess buddies from New Hampshire. What they were experts at was the process of using computers and chess programs. Together, they chose three or four possible moves and tested a series of combinations based on these in the different chess programs. When someone found a strong series of moves, they compared it in the different programs to see if it held up.

"Our main strengths were extensive opening preparations, knowledge of each chess engine used and how they evaluate certain types of positions, as well as database knowledge," they wrote after the win.

This type of chess is now called centaur chess, after the mythological creature that is half horse, half human.

This was not the only time Kasparov noticed this fascinating phenomenon, and he formulated it this way: "A weak human player plus machine plus a better process is superior, not only against a very powerful machine, but most notably, a strong human player plus machine plus an inferior process."

This has recently begun to be called Kasparov's Law.

Now, your goal in life may not be to become the best in the world at centaur chess but to use AI in your job and everyday life. Then I have good news. Together with Boston Consulting Group, Professor Ethan Mollick tested how consultants who do not use ChatGPT fare against consultants who use ChatGPT (centaur consultants). The over 700 consultants who participated in the test had to perform 18 different work tasks that are realistic examples of the type of work done at a consulting firm. Centaur consultants performed significantly better.

"In every way. In every way, we measured performance," writes Mollick. Consultants who used AI completed 12 percent more tasks, worked 25 percent faster, and produced results of 40 percent higher quality than those without. Even more interesting and directly related to the two chess amateurs is the answer to the question of which group benefited most from using AI. The consultants who scored the lowest at the beginning of the experiment had the biggest increase in their performance, 43 percent, when they used ChatGPT. Everyone improved their performance with the help of ChatGPT, but those who usually performed the worst improved the most.

Become a centaur

That's how we should think about AI tools like ChatGPT, Bing, Bard, Midjourney, DALL-E, and all the others. The person who becomes skilled at using them gains superpowers. A person who cannot paint by hand can create amazing artwork on the computer. A person who usually writes slowly and poorly can write quickly and well with the help of AI.

"Yes, but what should I write then? There's nothing worse for me than a blank page," you might feel. Then the AI helps you think too. And you don't need to know how to program or learn a new advanced way to control the computer. Your normal language is enough. The one you use in an email to a colleague.

But becoming good at using AI tools takes time and effort. Anyone can start using them and achieve a perfectly okay outcome. Give it some time and gain knowledge, and your results can quickly become really good. At a level you have never delivered before. Using AI tools correctly is like installing an update to your brain. A better, faster operating system.

The AI tools are so new that there are no established experts. Therefore, there are a lot of new things to discover. If you want, you can be the one making those discoveries.

Mathias Sundin

The Angry Optimist

Excerpt from "The Centaur's Edge – How to Think, Write, and Communicate Better and Faster with ChatGPT". Out soon.

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.