☀ Static electricity can "wash" solar panels in the desert

By using static electricity, it is possible to clean solar panels in deserts without using water. This means saving water that can provide two million people with drinking water.

Share this story!

Deserts are a great place to build large solar panel arrays. The sun shines brightly, it's rarely cloudy, no trees shade, and it doesn't take up valuable arable land. But there are some challenges. One of these is that the wind carries sand, which lands on the solar panels, which can reduce electricity output by up to 30 percent.

A common method of getting rid of the sand is to rinse the panels with water. Today, almost 40 billion liters are used to clean solar panels. It would be enough to supply two million people with drinking water in these areas, which can often suffer from water shortages.

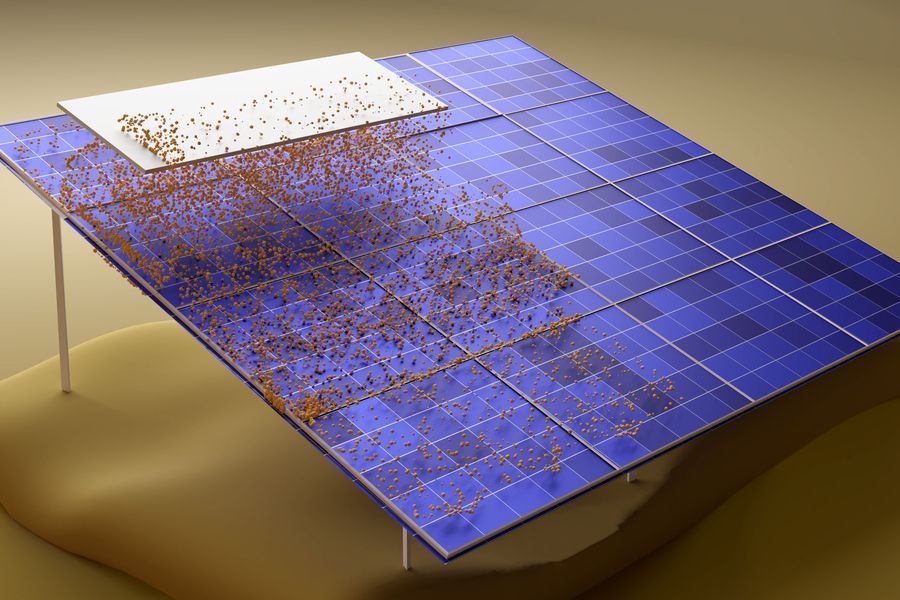

Now researchers at MIT in the US have found another solution to the problem. They have developed a method where they use static electricity instead of water. The static electricity repels the sand grains and keeps the panels sand-free.

Simply put, it works through an electrode that gives the sand grains an electric charge, and when voltage is sent through the panel, the particles are repelled. The whole thing can be taken care of automatically, so no staff needs to be sent out into the desert.

According to the researchers' calculations, as little as a percent reduction in electricity production from a 150 MW solar panel plant can cost the electricity producer around $220'000 per year in reduced revenues. If it is a three-four percent reduction, it would reduce revenues from all the world's solar panel plants in deserts by up to $5.5 billion. According to the researchers, sand can reduce production by 30 percent in just one month, so continuously cleaning the panels is very important.

"So much work is being done now to develop the materials for solar panels. They are trying to increase efficiency by a few percent, but our method can give much better results than that", says Kripa Varanasi, professor at MIT and one of the researchers behind the method, in a press release.

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.