🚛 The self-driving future is getting closer at Volvo

Volvo is facing its biggest shift since the company was founded. Instead of selling trucks, it now aims to sell transportation – with autonomous vehicles at the center of an entirely new ecosystem.

Share this story!

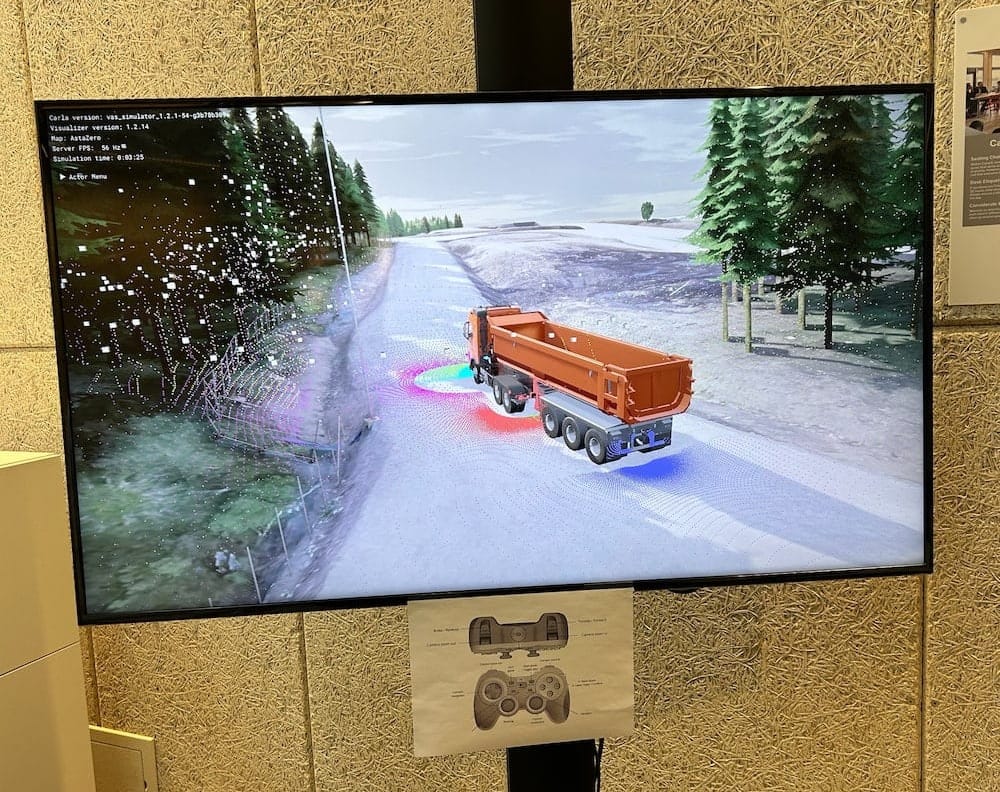

It’s an unusual environment consisting of both lubricating oil and advanced processors. At Volvo Autonomous Solutions in Gothenburg, you’ll find not only programmers but also mechanics. The digital and physical worlds merge there – in the form of trucks that can drive themselves.

This doesn’t just mean changes in the service bay; it requires Volvo to create a new business model. More than that – the entire global logistics system will be affected, and all of us will be able to receive products delivered faster, cheaper, and more sustainably.

To better understand this, I spoke with Volvo’s CEO, Martin Lundstedt (interview next week), and visited CampX in Gothenburg, where I met with the head of Volvo Autonomous Solutions, Nils Jaeger, and his CTO, Ingo Stürmer.

Nils Jaeger has led Volvo Autonomous Solutions since 2020. Earlier in his career, he worked for John Deere, where he was exposed to autonomous vehicles in the form of GPS-guided agricultural machines that enabled precision farming and higher yields from the fields. Autonomous technology entered agriculture earlier, giving him valuable experience as the same shift is now taking place in the transport industry.

“When we launched that technology on the market, we quickly realized this was something different,” says Jaeger. “You couldn’t just hand it over to a regular dealer to get it out to the market. We had to find new ways, new approaches, and new business models.”

Helping him is Ingo Stürmer, Chief Technology Officer. He has a background at DaimlerChrysler Research and Technology and also ran his own software company in Berlin for ten years. He later came to Sweden through a job at Einride and was then recruited to Volvo a few years ago.

What attracted him to Volvo was what he calls a realistic view of how to bring technology to market.

“Many companies in the autonomous space have failed not because of the technology, but mainly because of the business model,” says Stürmer.

If you simply have access to sufficiently advanced tools – such as aviation-grade lidar and military-level sensors, and so on – you can solve the technical challenges and make the vehicle drive itself, he explains.

“But then you end up with a product no one can afford, and in that case you can’t bring about any real change.”

The real challenge, then, is scaling up with much cheaper technology while maintaining, or even improving, safety to enter the market. Only then can real change happen.

“That’s why we’re taking a rather conservative approach,” says Stürmer, and Jaeger adds that they are first focusing on mining areas and highway driving for their autonomous trucks.

A dramatic shift

But behind this conservative, or somewhat cautious, approach lies a dramatic choice: Volvo plans to change its business model.

Put simply, today Volvo sells vehicles, but in the future Volvo will sell a transport service.

Of course, Volvo already sells services today, such as maintenance, training, connected systems, and financing. But the core is selling a vehicle. Tomorrow Volvo will sell transportation as a service, with autonomous trucks driving between terminals.

“In our view, you can’t just build a truck, add all the sensors, put in a virtual driver, and sell it to someone. That won’t work,” says Jaeger.

Instead, they plan to offer an entire ecosystem of services. The vehicle forms the foundation, where Volvo has its core competence. To this is added the virtual driver that Volvo integrates into its trucks for highway driving. To ensure high availability, Volvo’s established uptime services are used. Through its dealer network and service infrastructure, Volvo can guarantee that the vehicles remain operational.

At the operational level, capabilities are needed for fleet management: monitoring, control, route management, and the daily running of transport operations. Along with this come advanced fleet optimization systems, developed in-house by Volvo, to optimize the use of the vehicles—how many are running, where they are located, and how they are utilized.

Another key component is terminal operations, since transports often take place hub to hub. This requires efficient handling of transshipment. Finally, the entire system needs to be complemented with payment solutions and business systems so customers can manage and pay for their transports smoothly.

Together, these elements form an ecosystem where Volvo not only delivers vehicles but creates a complete solution for autonomous transport.

Partnership is the new leadership

The obvious risk is that Volvo becomes spread too thin and has to solve issues in areas where it has little or no prior competence. When I ask them about this, they answer immediately: Partnership is the new leadership.

A bit of a cliché, but they seem to practice what they preach. For example, while Volvo is indeed developing its own virtual driver, they are above all preparing the trucks to be able to connect with any virtual driver.

At the forefront in that category is Aurora, which earlier this year began delivering freight with fully driverless trucks between Dallas and Houston—making them the first company with a commercial autonomous trucking service on public roads. Aurora is a partner of Volvo.

Volvo will therefore not become a logistics company competing with DHL or DB Schenker. A logistics company plans, optimizes, and manages the flow of goods, including warehousing, order management, tracking, and distribution. But it will become a transport company, which can, for example, have DHL as a customer and carry goods for them from point A to point B.

A massive change

Self-driving vehicles will not only be a major change for Volvo but will affect all of us.

When trucks drive autonomously, the cost per kilometer decreases, but the biggest change is that variability goes down. Transport becomes smoother and more predictable, both in cost and time. Uncertainties caused by drivers, rest breaks, staffing, and scheduling are eliminated, making the entire chain more stable and reliable.

As more trips occur on standardized routes, accidents decrease, which lowers insurance costs.

For cargo owners, retailers, and industry, this means less need for buffer stocks and more reliable delivery times.

In other words, transporting goods will become cheaper, and consequently, goods themselves may become cheaper for us to buy them.

Flows will concentrate along defined corridors where the standard is high. Terminals will become central nodes where value is created through rapid transshipment, energy management, and efficient logistics.

Terminals will also become energy hubs. For electric trucks, large-scale planning is required, and standards for interfaces between vehicles and terminals will determine who can scale up the fastest.

So what happens to today’s haulers? There will be strong pressure on traditional long-haul transport between hubs, but at the same time, new opportunities will open. They can grow in shorter hauls, terminal operations, specialized transport, and by strengthening relationships with their customers.

One group clearly affected is drivers. But the transition will likely be less dramatic than one might think. Not all trucks will become autonomous overnight; the change will take place over several years. In addition, there is already a severe driver shortage, so for those who are in the profession, jobs will exist for years to come, most likely.

Regulate wisely, dear politicians

How regulations are designed will determine who moves fastest. What’s needed are long-term permits that make operators willing to invest in vehicles, terminals, and operating staff, as well as clear rules for liability, safety, insurance, and data sharing.

Countries and regions that designate autonomous freight corridors—with common requirements for vehicles, sensors, connectivity, road maintenance, and incident management—will attract capital and pilot projects ahead of others. The key is to move from short trial licenses to multi-year permits, harmonize regulations across borders, and require open data on punctuality, safety, and emissions.

For cities and regions, it’s about urban planning and permits that guide traffic to the right locations. This requires allocating space for terminals near major highways and simplifying construction and land-use permits. Energy will be a central issue: power grids and charging capacity must be built into the terminals, with grid connections, capacity subscriptions, and scalable charging zones.

If done properly, a clear map emerges: autonomous transport runs in designated corridors, turns around quickly in well-planned terminals, and relieves city streets, while at the same time investments and jobs flow to the countries and cities that make implementation easy.

Unfortunately, this is an area where the EU is clearly behind the US. It is in the US that Volvo has obtained a license as a transport company, and that is where its initial focus lies.

Become an AI maestro

I wrap up by asking Ingo and Nils how one can be part of this. If you find what’s happening in this industry exciting, where are the opportunities? What can you do yourself to get involved?

“There is a strong trend in software development toward broad knowledge rather than very specific tasks that an AI system can solve for you anyway,” says Stürmer. “Software engineers will increasingly take on the role of orchestrators. Instead of writing every single line of code themselves, they will assemble different components automatically generated by a system.”

Instead of learning to play the violin, you should be composing symphonies or becoming a conductor.

Mathias Sundin

Angry Optimist

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.