💡 Optimist's Edge: Prize competitions accelerate innovation

💡 Prize competitions accelerate innovation by both crowdsourcing ideas and financing.

Share this story!

📈 Here are the facts

Peter Diamandis had grown tired of waiting. It was the early 1990s, and we should have had bases on both the Moon and Mars. Tens of thousands of people should have been in space, not just a few hundred. As a little boy, he had watched the Moon landing, and Star Trek, and became a space nerd. Space development, which had moved so quickly in the 60s, had almost stopped by the early 90s.

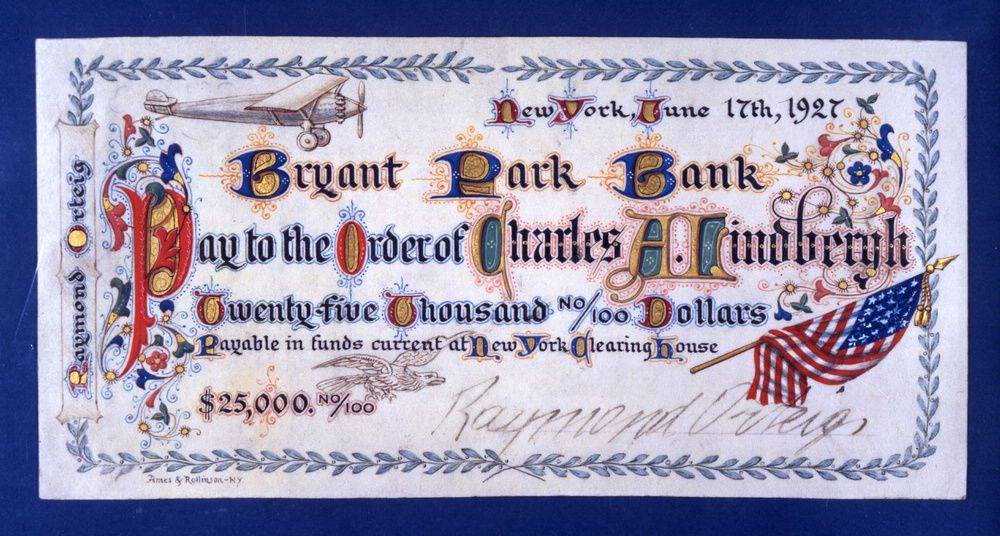

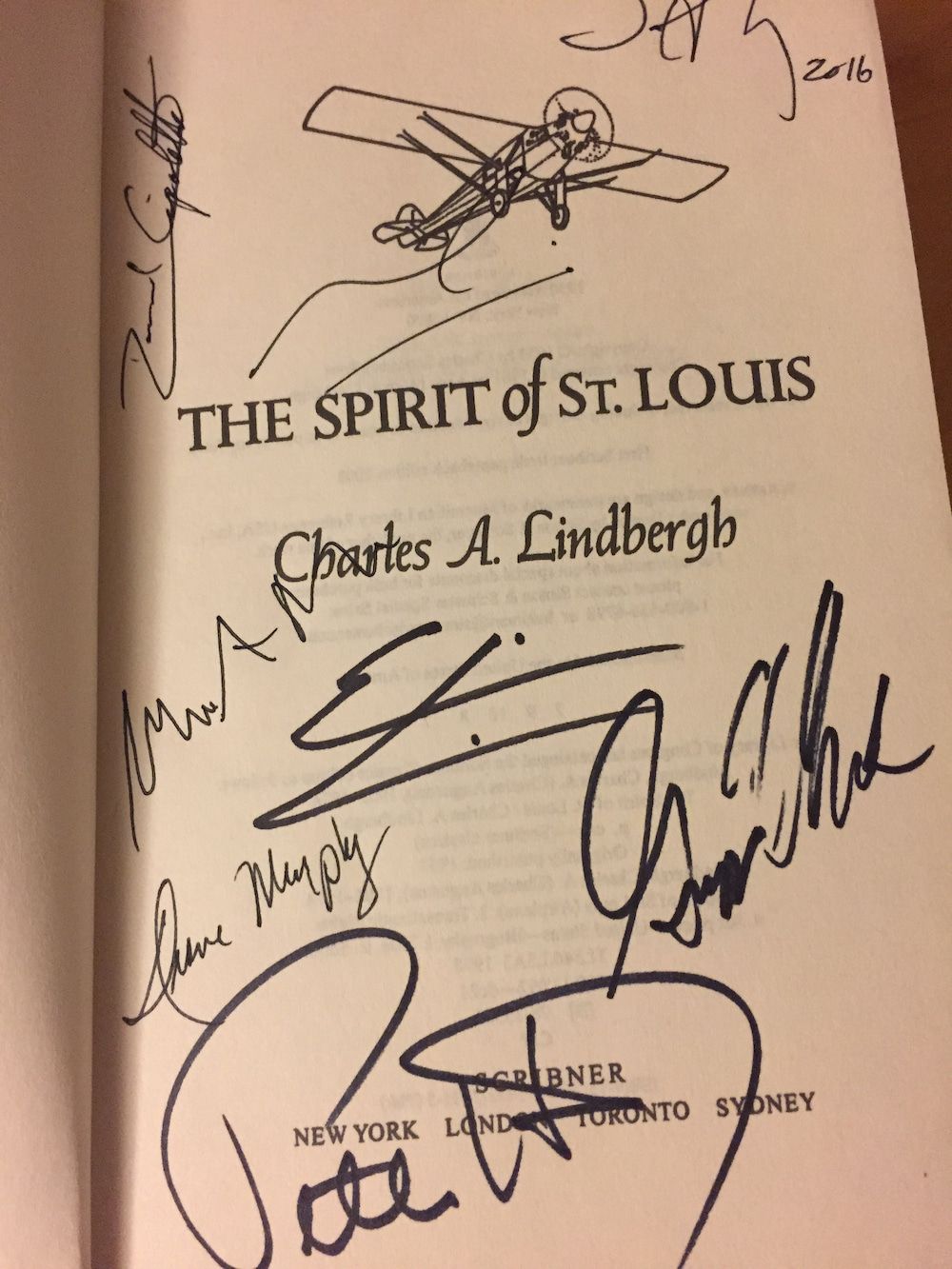

Somewhere around there, he read Charles Lindbergh's book, The Spirit of St. Louis, about the first Atlantic flight. He then learned that the reason Lindbergh flew over the Atlantic was to win a prize, The Orteig Prize. The hotel owner and aviation enthusiast Raymond Orteig had offered $25,000 to whoever first accomplished the feat.

Hmm, thought Diamandis, can I do something similar to speed up private space travel?

Said and done.

He put together a $10 million prize, which would go to the first private space flight. Together with Buzz Aldrin and other prominent people, he launched the competition in May 1996.

Since he lacked both prize money and a sponsor, the competition was given a temporary name: X Prize, where the X would later be replaced with the sponsor's name.

Despite this, several teams signed up. Among them one from the creator of Quake, John Carmack, and another financed by the Microsoft founder, Paul Allen. The 26 teams invested over $100 million together to win the competition.

Peter Diamandis pitched to over 500 people to sponsor the prize, but everyone said no.

In a desperate attempt involving a new Atlantic flight by Charles Lindbergh's grandson, Eric, an insurance policy, and a grant from the Ansari family, he finally got the money.

This bizarre and entertaining story is described in the book How to Make a Spaceship.

In October 2004, the competition was won by Paul Allen's team, Scaled Composites. By then, Richard Branson's Virgin had bought into the team. After the competition, it became Virgin Galactic, and when Branson flew to space in 2021, it was in a spacecraft based on the one that won the competition.

Because it took several years to find a name sponsor for the competition, the X stuck, and the X Prize Foundation has now, for over 20 years, run several prize competitions.

💡 Optimist's Edge

💡 Prize competitions accelerate innovation by both crowdsourcing ideas and financing.

In many prize competitions, the amount invested by all teams is often considerably larger than the prize amount. Not infrequently 10 or 20 times larger. For The Orteig Prize 16 times. In other words, you get a lot of bang for your buck.

Even more important is the diversity of ideas. In "regular" innovation, it is usually those who work in an area who tinker with it, but in a competition, others get the chance to test their ideas. Scaled Composites, who won the Ansari X Prize, had not done anything in space before, they built airplanes.

A properly designed prize competition attacks many brains and money bags and push innovation forward.

👇 How to get the Optimist's Edge

There are two main options. Organize your own prize competition, or participate in one.

There are a number of prize competitions around the world.

- X Prize currently has four competitions underway. Among other things, about forest fires and one about carbon capture with a prize pool of one hundred million dollars, sponsored by Elon Musk.

- DARPA regularly works with prize competitions.

- The European Social Innovation Competition has competitions in the social field, right now about energy poverty.

- Milken Institute is now running competitions in green energy and the UN's sustainability goals.

- At the Innovation Challenge, those who are creative in reducing food waste can win a prize.

Proper design is important

A competition in an area where there is already a lot of innovation is unnecessary. We do not need a competition for generative AI right now, for example. The focus should be where innovation has stagnated and new, fresh ideas and a concerted effort can really push it forward.

The design of the criteria for victory is extremely important. The goal must be ambitious, but not unattainable. It must be clear and should not be possible to circumvent and find a way to win that does not really benefit the purpose of the competition.

Often there are both interim goals and final goals. Since a competition can last several years, financing is often a problem for the teams competing. There, interim goals with some prize money can help. It may also be that several ideas are good, and in the long run, an idea that did not win the final prize may still be the most successful. Then it can be good to spread prestige and money a bit.

After innovation comes implementation

Innovation is one thing, and implementation is something else. It took almost twenty years for Virgin Galactic to go from the first successful journey to space in 2004, to getting the first private individuals into space. They have not yet regularly started flying space tourists.

DARPA kicked off the area of self-driving cars with its DARPA Grand Challenge. Despite this, we do not yet have fully autonomous vehicles on the roads, even though Tesla, Waymo and others are working on it.

Both when planning a competition or participating in one, you should think about what comes after the innovation, after the breakthrough.

Mathias Sundin

The Angry Optimist

You now have an advantage because you have gained this knowledge before most others –