🚛 How he is leading Volvo through its greatest transformation ever

He leads Sweden’s largest company, which has been selling trucks for nearly a hundred years. Soon, they’ll stop doing that — and instead sell transport as a service. How do you lead such a massive company through that kind of transformation?

Share this story!

At the first official meeting of the Swedish government’s AI Commission, Martin Lundstedt couldn’t join the morning study visit. He had a good reason for his absence. Lundstedt was busy presenting Volvo’s full-year results for 2023 — along with the largest dividend in Swedish history. Volvo, where Lundstedt is CEO, performed so well that it paid out 37 billion SEK ($4 billion) to its shareholders.

But after lunch, he showed up. We were both members of the commission, and when he sat down next to me, I was tempted to ask a sports-style question: How does it feel?

I didn’t. Instead, we dove straight into a discussion about AI. For a major company like Volvo, with over a hundred thousand employees, AI has countless implications — but roughly speaking, it affects them in two ways: First, generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Copilot become part of employees’ daily work. Second, artificial intelligence is being built into the vehicles themselves.

There are many aspects that fascinate me. When a new technology like generative AI emerges, how do you implement it across a large organization? And the classic dilemma: when new technology ultimately undermines your current business model, how do you lead the company toward a new one?

There wasn’t time to explore all of this during the AI Commission meetings, so while writing my book The Fifth Acceleration, I interviewed Martin Lundstedt. I also visited Volvo Autonomous Solutions in Gothenburg and spoke with Raquel Urtasun, founder of one of Volvo’s partners, Waabi. They use generative AI to create a digital testing environment for self-driving vehicles.

Some of these insights are included in the book, but a more detailed account can be found in two articles here at Warp News. The first covers my visit to Volvo Autonomous Solutions, and this one shares my conversation with Martin Lundstedt.

Worked his ass off

Martin Lundstedt has the kind of personality that immediately puts you at ease — despite the fact that he runs Sweden’s biggest company. That’s not to say he’s soft. Working your way up from a trainee position at Scania to CEO — first at Scania, and later at Volvo — takes serious grit.

I begin by asking him about his driving force.

He developed an interest in business early in life.

“I grew up in an entrepreneurial family. Both my paternal and maternal grandparents ran their own businesses,” he says.

He got a crash course in business through a bankruptcy. After high school, he worked at a small company that happened to go bankrupt. It had about fifty employees, but only a handful in the office — the rest worked out in the field. The bankruptcy trustee had several other cases to handle, so the responsibility to keep the firm running fell to Martin Lundstedt.

“I learned more during those six or seven months than I did in several years at Chalmers. A lot about doing business and understanding what really matters.”

Somewhere around that time, he fell in love with business itself — but after earning his master’s degree in engineering at Chalmers, he went into heavy industry. It was 1992, a time of economic crisis in Sweden, but he managed to land a trainee position at the truck manufacturer Scania.

Since then, he has, in his own words, “worked his ass off.” But he also worked broadly, taking on many different roles. He didn’t stick to one track but led production in France, sales in Brazil, and worked with engine development. That breadth was one of the main reasons Volvo wanted him as CEO, according to then-chairman Carl-Henric Svanberg.

After just twenty years, he reached the top and became CEO of Scania. Three years later, he was lured over to rival Volvo. According to Dagens industri, roughly one hundred billion dollars in shareholder value has been created during his tenure.

His interests go beyond business. Transport and logistics, he says, shape entire societies.

“We know that advanced logistics lead to faster growth, which increases prosperity, but it also has to become more sustainable. That makes you feel like part of a sector that is part of something much bigger,” he says.

When he became CEO of Volvo, it was a company with low profitability — far below Scania, for example. It has been a transformation journey ever since, and such a journey never really ends, especially not when something as transformative as AI enters the picture.

Lundstedt explains that in Volvo’s work with AI and digitalization, change management isn’t about chasing new technology for its own sake, but about creating structure and accountability. Just as Volvo has always had a clear map for its products — with platforms, components, and how everything fits together — it has now built a corresponding structure for the digital side. They call it a “stack”: essentially an overview of the layers of systems, data, and tools that must work together. It means that data is collected in one place, quality-assured, and made available for analysis and AI, allowing management to understand and steer development much as they do with trucks and excavators.

“We’ve spent a lot of time making our digital stack a mirror of our product stack, so that we speak the same language — how we need to manage, develop, recruit talent, and understand the components required to meet our commitments,” Lundstedt says.

Ten years ago, when Volvo was struggling, the need for change was obvious. Now, with high profitability and debt turned into a large cash reserve, it might be tempting to stay the course. But instead, Volvo is moving toward an entirely new business model, as I described last week:

Put simply, Volvo today sells vehicles — but in the future, Volvo will sell a transport service made up of autonomous vehicles.

As someone who once failed as CEO of a company with just three employees, I can’t help but marvel at how one leads more than 100,000 people — especially through such a massive transformation.

It’s a balancing act between decentralization and shared direction.

“Volvo is a mosaic of small companies,” says Lundstedt. “When you put the mosaic together, you see the Volvo brand. But when you zoom in, you see all the small companies.”

That gives each team a sense of ownership over its part of the whole, even within such a large organization.

That sounds easy in theory, but of course it’s much harder in practice.

“In school we learned that the more volume you have, the lower the unit cost. And that’s true — but when things get too big, other problems arise. Bureaucracy, bullshit, steering committees and decisions being made at the wrong level. So the key is to balance the two and be very disciplined about it.”

Some things need to be shared across the company, while others can differ depending on where in the organization you are. The values, for example, must be the same.

“You can’t have one code of conduct in Romania and another in the U.S.,” says Lundstedt.

A key role for the CEO, then, is to maintain a bird’s-eye view — to distinguish what’s important from what’s not.

“Sometimes large organizations can become exactly wrong rather than approximately right.”

In other words, they can become obsessively precise about details that don’t matter — and miss what truly does.

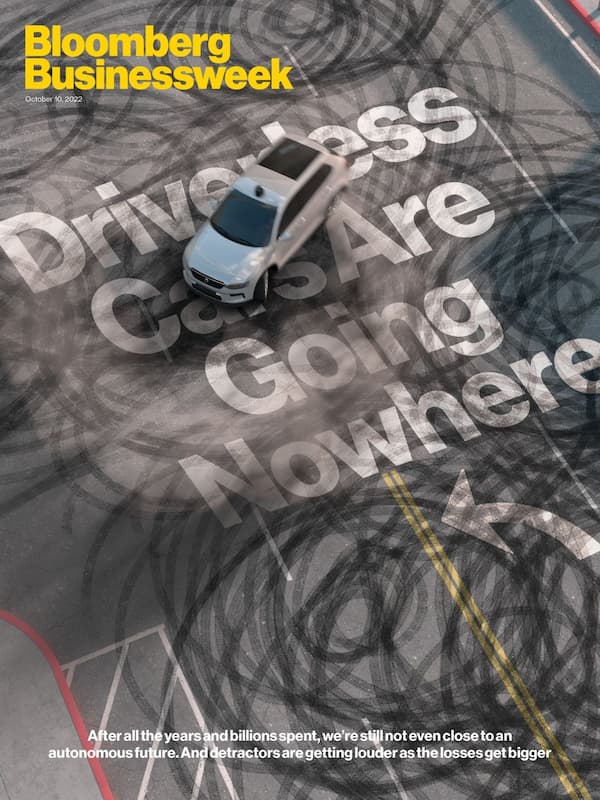

That mindset, I think, also relates to the decision to gradually shift Volvo’s business model. If you get caught up in the details and focus too closely on the development of self-driving vehicles, it looks like a roller coaster of big hopes and crushed expectations — swinging from believing a breakthrough was only a few years away to the opposite.

Captured perfectly by this magazine cover from 2022.

But if you zoom out and free yourself from the details, you see steady progress.

Volvo has also identified a path forward that’s less complex than passenger cars: hub-to-hub transport, mostly on highways.

“Compared to other use cases, it’s less complex — even though it happens on highways and in public traffic. These are still relatively controlled environments, with defined sending and receiving areas before the trailer is connected,” says Lundstedt.

And then, regulations — again

There is, however, one major obstacle to the autonomous future: regulation.

Volvo’s transition from vehicle manufacturer to transport-as-a-service provider is starting in the U.S. Not solely because of regulations, but partly. Within the EU, the regulatory landscape is much more tangled, which is why there’s far less development and testing of autonomous vehicles here.

Lundstedt says he spends quite a bit of time talking with people in Brussels about this. The technology being developed already makes traffic safer and vehicles greener — but if regulations prevent it from being fully used, it doesn’t matter.

He prefers horizontal regulations — those that apply across many sectors — over vertical regulations, which target specific industries such as transport. Horizontal rules make it easier to build a broad ecosystem where many actors, from major corporations to startups, can collaborate under a shared framework. Vertical, sector-specific rules risk colliding with each other and creating contradictions.

The regulation mirage

I’ve often argued, here and elsewhere, against the exaggerated belief in pre-emptive regulation of new technology. Regulating in advance mostly acts as a brake on innovation.

With self-driving vehicles, this becomes obvious. There is now plenty of data showing that autonomous vehicles are already safer and cause far fewer accidents. The purpose of the EU’s regulations is to make citizens safer through “responsible” development. But in practice, it slows progress — and the safer vehicles operate in other countries, outside the EU. The result is that EU citizens are left with less safe roads for longer.

Regulations certainly have a place in society, and many make our lives safer or protect us from corporate abuse. But regulating before new technology has matured usually achieves the opposite.

The self-driving future is getting nearer

I’ve followed the development of autonomous vehicles quite closely for more than a decade. In 2016, I hosted a seminar in the Swedish Parliament together with Volvo Cars (a separate company from AB Volvo) to discuss self-driving cars.

Back then, there were many players and a great deal of optimism. In the early 2020s, the pendulum swung the other way — some major players, like General Motors, shut down their programs.

The technology isn’t there yet; it’s not good enough to transform the world. But progress hasn’t stopped — or even slowed. If you look past the headlines, you’ll see that we’re much closer now than we were ten years ago. The pessimism comes from unmet expectations, not from stagnation.

My visits to Volvo Autonomous Solutions and my conversations with Martin Lundstedt haven’t changed my view — they’ve strengthened it. We are approaching a dramatic shift in transport and logistics: a world where all vehicles drive themselves and are powered by electricity. It won’t happen overnight — it will take decades — but the direction is clear.

Mathias Sundin

Angry Optimist

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.