🌕 Finally, FINALLY, we’re heading back to the Moon (with the goal of staying)

This is Artemis II and an interview with Sweden’s first astronaut, Christer Fuglesang.

Share this story!

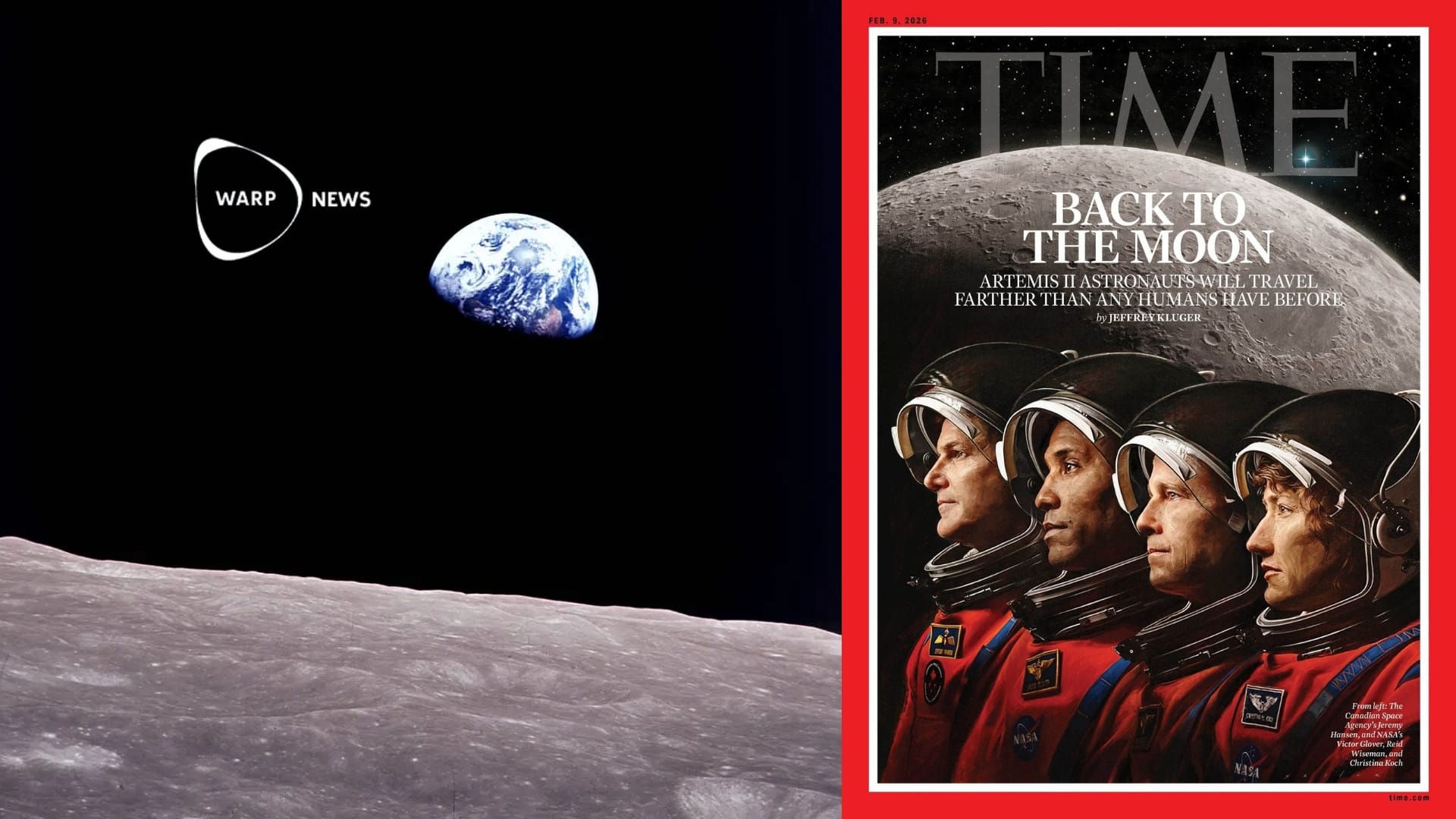

For the first time in more than 50 years, a group of humans will leave Earth and travel to the Moon. There are four people on the mission, and they include the first woman, the first Black person, and the first Canadian.

Before you get too excited — they will not land. They will “only” fly around the Moon. This is the preparatory mission, equivalent to what Apollo 8 was before Apollo 11.

Even though they won’t land, this mission is a big deal. Since 1972, no human has traveled farther from Earth than low Earth orbit. The farthest any human has been from Earth since Apollo 17 is 1,400.7 kilometers from Earth’s surface. That altitude was reached on September 11, 2024, during the private space mission Polaris Dawn.

Artemis II, which is the name of this mission, will take the four astronauts farther from Earth than any humans have ever been. Artemis II is planned to reach a maximum distance of about 413,000 kilometers from Earth.

The exact distance depends on where the Moon is in its orbit at the time of launch, but the plan is for the Orion spacecraft to fly roughly 7,400 kilometers beyond the far side of the Moon.

The current record for the greatest distance humans have traveled from Earth was set by the crew of Apollo 13 in 1970. They reached a distance of 400,171 kilometers when they rounded the Moon to return home after their accident. Artemis II will therefore break this record by more than 10,000 kilometers.

Apollo 8, which preceded the Moon landing of Apollo 11, also gave us one of the most iconic photographs of all time: Earthrise.

On Christmas Eve 1968, as their spacecraft emerged from behind the Moon, astronaut Bill Anders looked out a window and saw something no human had ever seen before. He saw the Earth “rise.” Instead of the Sun rising, it was the Earth emerging from the black void.

Seeing Earth like that — a Christmas ornament suspended in the vastness of space— did something to both the astronauts and the people back on Earth.

It made us more deeply realize how small and fragile our home is, and that we should take better care of it. The environmental movements of the 1960s were strengthened by the photograph, and it was used when Earth Day was established.

We went out into space to explore the Moon, but discovered Earth.

We don’t know everything we will discover during Artemis II, and that is a crucial part of why exploration is so important. It’s only when you are there that unexpected insights emerge.

After Artemis II comes, logically enough, Artemis III — and then we will land. That is when the first woman will step onto the surface of the Moon.

The long-term goal now is to stay

A decisive difference between Artemis and Apollo is that the long-term plan this time is to establish a permanent human presence on the Moon.

This will be done through a step-by-step build-up of infrastructure. The process begins in orbit with the Lunar Gateway space station, which will be crewed. On the lunar surface, the permanent presence will take shape in the early 2030s through two critical steps:

- With Artemis VII, a pressurized rover will be delivered (developed by the Japanese space agency JAXA and Toyota). This will function as a mobile motorhome where astronauts can live and work in a “shirtsleeve environment” (without spacesuits) for up to 30 days, dramatically increasing the range of exploration.

- Then comes Artemis VIII, when a fixed habitation module will land. It will be able to house four astronauts for extended periods and will form the core of the base camp.

After that, more buildings and capabilities will gradually be added.

Since November 2, 2000, when the first crew arrived at the International Space Station, at least one human has always been in space.

From the 2030s onward, there may also be humans permanently on the Moon.

When Reid Wiseman, Victor J. Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen lift off from Kennedy Space Center, it is hopefully the beginning of a new era for humanity—one in which we exist on two celestial bodies.

Interview with Christer Fuglesang

Sweden’s first astronaut is spending time with his grandchildren, but gets back to me the following day with answers to my questions.

Why has it taken more than 50 years since we last went to the Moon?

“The reason the United States (it wasn’t really ‘we,’ but people like to feel it was all of humanity) went to the Moon in the 1960s was that they felt compelled to show themselves and the world that they were better than their archenemy, the Soviet Union, in the middle of the Cold War. This became a very large and important national undertaking, for which the U.S. was willing to spend enormous sums of money.

When the goal was achieved (which had nothing at all to do with research, although that became a very positive side effect), it was not feasible to continue spending several percent of the national budget on it. The idea was to first build cheaper ways of getting into space, which became the Space Shuttle. However, it never became cheap.

But today, one could say that technology has finally caught up with economics, and it is no longer unreasonably expensive to travel to the Moon. Another reason is that there was no geopolitical competition over the Moon until recently, when China also announced that it intends to send humans there.”

These astronauts will not land on the Moon, but fly around it. Can you describe what is special about this journey and what NASA and the other Artemis partners hope to learn from it?

“There is nothing particularly special from a research or exploration perspective. The same journey was first made in 1968 with Apollo 8, which even entered lunar orbit—something Artemis II will not do. But there are a couple of new aspects: it is international (Apollo was 100 percent national and American), with a Canadian astronaut, and the service module for the Orion capsule is European.

The main purpose is partly to test that everything works with a crew onboard (Artemis I tested most systems uncrewed in November 2022) and to demonstrate that we are now beginning the journey back to the Moon.”

The difference between then and now is that this time the long-term goal is to stay and establish a permanent presence on the Moon. What is required for that, compared to “just” making individual trips?

“More logistics at the beginning. Water, oxygen, food must last longer. Power supply systems. Then building systems to recycle waste products (urine, exhaled carbon dioxide). Much of this has been developed on the ISS and can be applied, or modified, for the Moon.

In the long run—the holy grail—is to learn how to use the Moon’s own resources, which are quite limited. Very little water, for example, but with new smart technologies it will be possible. ISRU—In-situ Resource Utilization, as it’s called.”

Which space news do you think is bigger: that I’ve been elected to the board of the Swedish National Space Agency, or that we’re going back to the Moon?

“Mathias on the Space Agency board! More unexpected than ‘us’ finally heading back to the Moon again. ☺️”

Mathias Sundin

Angry Optimist

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.