☠️ Doomsdays That Never Happened

Humanity does seem to have a soft spot for the thought of its imminent destruction. Fortunately, we have beaten the odds of doom and gloom more than once...

Share this story!

Premium Supporters - click here to listen to the audio of this text.

If you’re reading this, congratulations. You have survived the apocalypse for the simple reason it never happened.

Perhaps we should be used to doomsday predictions gone wrong by now, but humanity does seem to have a soft spot for the thought of its imminent destruction. Throw out a “within ‘x’ number of years, you will...” and add a torturous fate, like be buried under a sheet of ice or go blind by unfiltered UV-light, and you’re bound to capture people’s — and the news media’s — undivided attention.

History is indeed filled with doomsters. When Harvard biologist George Wald in 1970 ominously predicted, “civilization will end within 15 or 30 years unless immediate action is taken against problems facing humankind,” he was hardly onto anything new. While superstition fueled the cataclysmic fears of previous generations, modern-era doomsday scenarios often fail to recognize human ingenuity, assuming instead we are held hostage by forces our actions supposedly unleashed.

Fortunately, we have beaten the odds of doom and gloom more than once. Cue the examples.

Beware of the flood

For a sense of perspective, let’s jump back to Feb. 20, 1524. On that day, Johannes Stöffler, a German mathematician and astronomer, had predicted a flood was going to engulf the world. As a light drizzle fell, people fought tooth and nail to board a three-story ark that had been built on the Rhine. At the end of the day, more people perished in the mayhem than in the actual flood, which never came. Stöffler, undeterred, then changed his prediction. Death by wave would eventually arrive, he pledged. Just wait 30 years.

Comet: Incoming

The worldwide panic of 1910 contained all the familiar ingredients of doom, including headlines like, “Comet May Kill All Earth Life, Says Scientist.” Gas masks flew off the shelves. Safe rooms popped up. Bottled air became a hot commodity. And in Oklahoma, a virgin was nearly sacrificed in an effort to stave off the impending disaster — Halley’s Comet and it’s poisonous cyanogen tail hurtling toward Earth. In the end, those who reportedly favored roof parties over hiding underground made the right call.

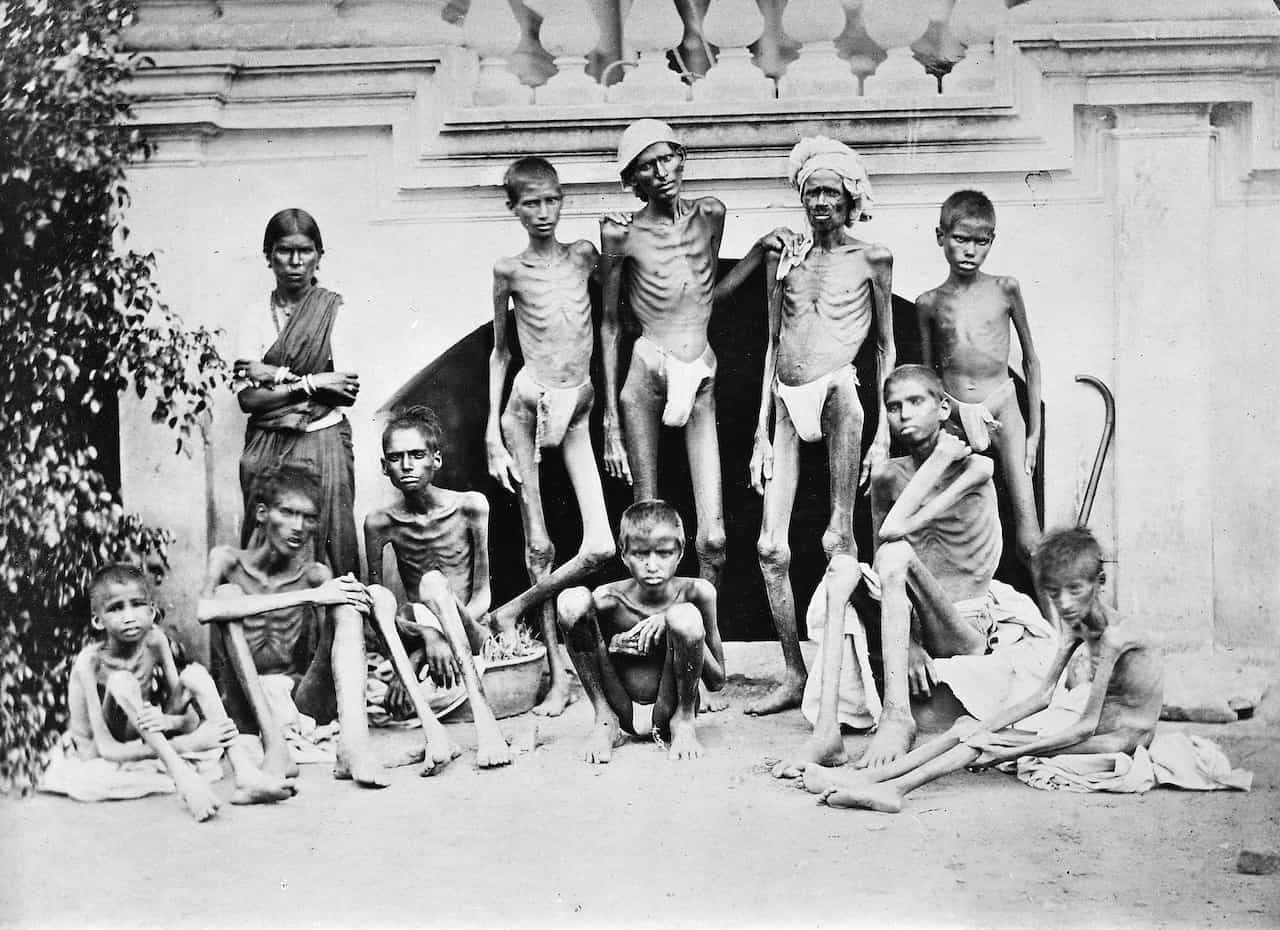

You’ll all starve

Between 1980 and 1989, some 4 billion people, including 65 million Americans, will perish in the “Great Die-Off.” That mother of all doomsday predictions belongs to Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich, who made a name for himself in the 1970s with a torrent of apocalyptic statements about our volatile relationship with nature. Ehrlich was in good company.

The threat of the “population bomb” sent the world into a froth around the time Earth Day was founded. Looking at the year 2000, doomsters foresaw mass starvation so horrific and widespread that one Pulitzer Prize winner even suggested — in the spirit of the nuclear arms race — that “To some overcrowded populations, the bomb may one day no longer seem a threat, but a release.”

So what actually happened? Even as the global population grew from 3 billion in 1960 to 7.6 billion today, per capita calorie supply has been consistently increasing, especially across poorer regions in Asia and Africa, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. At the same time, the total fertility rate has plunged below replacement level in some industrialized nations and dipped to 2.6 in the developing world, down from 6.06 in 1950.

Ozone hole terror

It was the horror story of the late 20th century: Earth’s natural sunscreen was disappearing, causing sheep to go blind, bunnies to turn into zombies, and the skin of south Chilean ranchers to “boil like water.” All eyes turned to the growing ozone hole (which is only a hole in a metaphorical sense) over the South Pole, measurements were taken, and grim predictions made.

“It’s like AIDS from the sky,” Newsweek quoted one terrified engineer of saying in 1991. Even back then, some of the most supernatural claims were dismissed as “too much Chicken Little and not enough Galileo,” but fear of the ozone hole was real. Would the protective bubble vanish and celestial elements forever extinguish humanity and life on Earth?

So how did it turn out? These days, Smithsonian magazine notes, scientists know a lot more about the ozone hole and its seasonal fluctuations. The hole is expected to heal completely by 2050, much as a result of the Montreal Protocol, a treaty signed in 1987 to phase out ozone-depleting chemicals, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), from products like hair sprays and refrigerators.

It’s freezing – or not

No child of the 1980s can forget the impending doom of the new ice age. Every cool breeze became a prelude to what was to come. It really is getting colder, isn't it?

The predictions were, after all, as consistent as they were dire. Boston Globe, 1970: “Scientists predict new ice age by 21st century.” The Guardian, 1974: “Space satellites show new ice age coming fast.” New York Times, 1978: “International team of specialists find no end in sight to 30-year cooling trend.”

In Newsweek, scientists also sounded the alarm on smokestacks and jet planes that they said were spewing so much pollution into the atmosphere that, “Screened from the sun’s heat, the planet will cool, the water vapor will fall and freeze, and a new Ice Age will be born."

We all know the result. Fears of the deep freeze melted away, but the doomsday headlines kept coming, only now heat was the real threat. (Salon, 2001: “New York City’s West Side Highway underwater by 2019”).

No hoarding please

The Y2K scare reads like a sci-fi novel, starring techies, preppers, and government command centers. Would the feared coding error — the Millennium Bug — finally finish us off as the clock struck midnight on December 31st? Would out-of-control computers send planes diving? Would nuclear missiles self-launch? The world was on edge (credit where it’s due: some level-headed individuals maintained it was a big hoax), basements filled with non-perishables, and officials begged everyone to stop hoarding.

By the time we reached the anticlimactic ending — nothing happened! — governments around the world had spent the equivalent of $448 billion in today’s money to counter the threat. And somewhere in Texas, a dad featured on the local news, who had gathered enough supplies to stock a convenience store, threw a big party to empty his mega freezer. “We ate it all.”

Don’t choke

The 1970s was not a pretty decade for the environment in the United States. Smog choked many American cities and rivers filled with raw sewage. It all provided fertile grounds for gloomy predictions. In 1970, Life wrote scientists had solid evidence that, within a decade, urban dwellers would need gas masks to survive air pollution. An ecologist in Time chimed in that it was only a matter of time before all land became unusable. And star doomster, Paul Ehrlich, pinned the estimated 1973 death toll in “smog disasters” in New York and Los Angeles to 200,000.

What does hindsight tell us? The smog has lifted and rivers are, for the most part, once again fit for fishing and swimming. In 1999, a Department of Interior analyst concluded after surveying emissions: "Cleaner air is a direct consequence of better technologies and the enormous and sustained investments that only a rich nation could have sunk into developing, installing, and operating these technologies."

Since then, much has happened. Electric vehicles reduced oil consumption by almost 600,000 barrels per day in 2019 and EV sales are expected to set a new market share record in 2020, according to the International Energy Agency. There’s more to this part of the story but we’ll save that for another time.

For now, the apocalypse has been called off. ☀️

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.