🎄 Christmas through the ages – A story about how things have gotten better

The ham and the pickled herring are on the table, and the bread is baked. Add to that Christmas beer, and Swedes would recognize it as a typical Christmas, regardless of whether you looked into a home this year, a hundred or two hundred years ago. So what has changed, and what has improved?

Share this story!

The similarities are many, as are the differences. Even if the nostalgic look back on the Christmases of their childhood and think that "it was better before," there is also value in looking at how the development has progressed. Because it has really progressed.

Democracy, rights, and living conditions have developed in a very positive direction over the last 200 years, and technological progress has given us opportunities to accelerate that development even further.

Then came the Coronavirus. Few things have had such an impact on society as Covid-19 in recent years. Remote working, layoffs, travel restrictions, canceled concerts, parties, rehearsals, a cultural sector in free fall, healthcare that has been strained to the breaking point, and most importantly, all the people who have fallen ill and the thousands who have passed away.

For Christmas, we still gather, albeit in smaller crowds this year as well. We summarize the past year and look ahead. Maybe we upgraded our baking talents during the period when everyone stockpiled flour and yeast, and perhaps those who hoarded toilet paper can turn it into some kind of creative decoration? We get cozy and find a sense of security and joy in traditions that we experience have been there since ancient times.

Ancient times is a truth with modification, by the way, as most Christmas traditions we have today have developed during the 20th century.

What was better in the past is quickly calculated. A few flashbacks give an idea of how the development has progressed and that the future looks even brighter.

Christmas 1820 – on a farm in south Sweden

During the beginning of the 19th century, neither Advent candlesticks nor Christmas tree decorations were known in the Swedish countryside. Most people worked hard and were happy if there was food on the table. But even in the simplest crofts, Christmas was still a big holiday that was celebrated properly.

Nobody knew who Santa Claus was at this time. The "Santa" they knew was a small harsh gnome that lived on the farm. Instead, it was the Christmas goat that handed out presents, if you happened to belong to a rare well-to-do family, that is. Rather than gifts, it was the Christmas food you looked forward to.

The book "Christmas in Skåne in the 1820s" by Nils Månsson Mandelgren describes the types of bread that were baked, the pig that was slaughtered, and how everything was taken care of, how the floors were scrubbed, cleaned, and strewn with sand and juniper.

In the months before Christmas, the working days were particularly long and burdensome. Potatoes and beets were harvested, the farmland plowed, firewood cut, and the animals fed extra rations. The threshing was finally done, and it was crucial that everything was finished before Christmas. On December 21, the strict little gnome's contract expired, and after that, he did not want to guard the grain anymore. Christmas was associated with a lot of superstition and magic, and therefore it was important that everything was taken care of properly.

In the last weeks before Christmas, the household was in full swing, and the slaughter was an important part of the preparations. Everything was taken care of, and sausages, press jam, blood sausages, lung puree, flatbread, and much more were made. If anything from the pig was left over, it was buried under a rock so that the stern gnome would be kept happy.

Among the more affluent, stearic candles were lit, but most used candles made from the tallow from the slaughter, the lard, and the smell must have been anything but pleasant. In addition to the religious elements with prayer, hymns, and Bible reading, superstition took a shockingly big place. The one whose candle first burned out would be the first in the house to die, and the comming year's events were also predicted in the ashes from the stove.

On Christmas Eve, it happened that the neighbors' servants snuck into the yard and intimidated the household by firing gunshots. If anyone from the household managed to catch them, they were offered food and drink.

Elsewhere, there was a tradition of sneaking into the yards, throwing in firewood with more or less vicious rhymes attached, and then running away before being recognized.

Early on Christmas Day, it was tradition to go to the early service in the church, and the days after, there were festivities where the farms invited each other. The festivities lasted until the "twentieth day of Knut" and were the year's only longer continuous holiday.

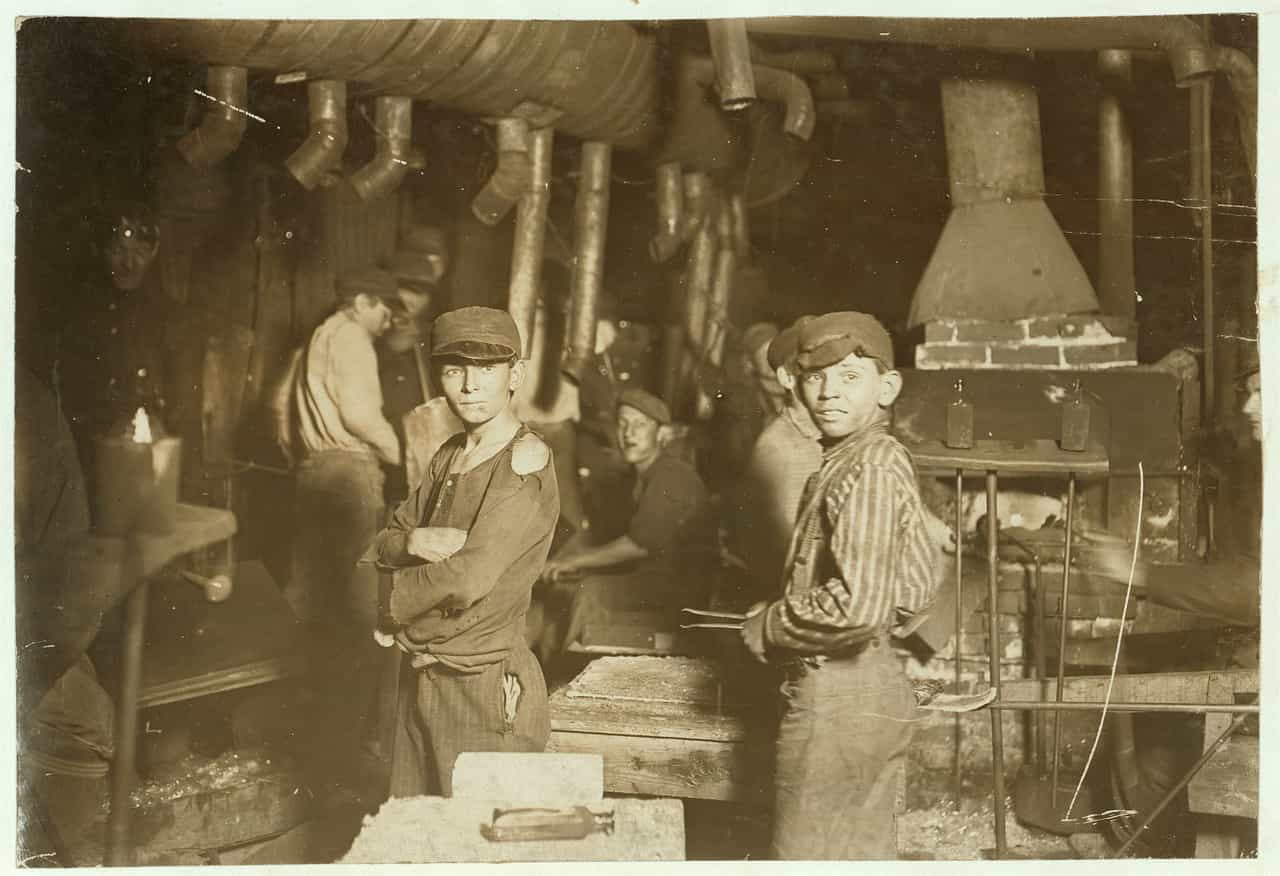

During the middle of the 19th century, Sweden began to industrialize. While in the countryside, people worked based on season, the relationship between factory owners and the labor force was governed by working hours. Child labor occurred, and even after regulation in law 1886, young people from the age of 14 could work twelve hours a day.

At the same time, the Swedes got a better standard of living and lived longer and longer, something that Esaias Tegnér attributed to "Peace, the vaccine and the potatoes."

The vaccine, in this case, was against smallpox, which had ravaged humans for at least 3,000 years. It is estimated that during the 20th century alone, at least 300 million people globally died of smallpox.

The first smallpox vaccination was carried out in Sweden in 1801, and in 1816 it became mandatory to vaccinate all children against smallpox. The morbidity of smallpox in the country decreased as a result of this very significantly. However, epidemic outbreaks, such as those affecting the elderly, occurred throughout the 19th century.

The life expectancy of someone born in Sweden in 1820 was about half compared to 2019.

On average, men died just before 40, while women became a few years older.

Child mortality was around 26 percent; more than one in four children died before the age of five.

Only around 10 percent of the world's population was literate.

Most people in Sweden lived a hard life with hard work, malnutrition, and without what we today consider the most basic health care. Many were involved in the grief of losing a child.

For many, Christmas meant a short break from a hard and strenuous everyday life. A moment of festivity before the work started again.

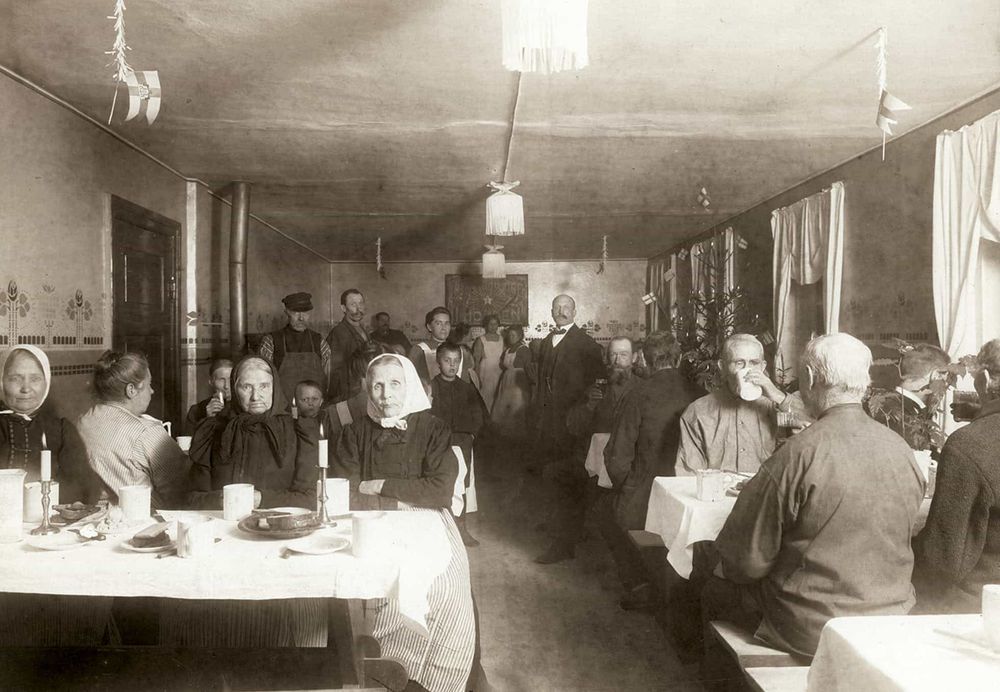

Christmas 1920 – with the Hallwyl family in Stockholm

Between Norrmalmstorg and Dramaten in Stockholm, Walther and Wilhelmina had built their winter home, which was completed in 1898. The years in the house are well documented, and Christmas 1920 offered a stylish experience in a palace environment.

The Christmas tree was traditionally bought on Norrmalmstorg and decorated with a star at the top and with candles, angels, baubles, glitter, and confectionery from Oscar Bergs Konditori. At the Christmas supper, men and women sat apart and were served ham, lye fish, butter, bread, and butter cake.

It is more uncertain whether there was a Christmas calendar in the house when the first Christmas calendar was launched that year in Germany. Hallwyls was one of the richest families in the country, but for the vast majority, Christmas 1920 was the end of a hard year.

The Spanish flu had come in another wave in the spring, and since its inception in 1918, the disease had claimed over 30,000 lives in Sweden. Globally, between fifty and one hundred million people lost their lives, far more than the ten million lost during World War I (1914-1918).

A couple of years ago, the counter-book, motboken in Swedish, had begun to be introduced to reduce drinking, which also led to fewer violent crimes. However, it also had a strong class-dividing effect where the rich were given greater rations and in addition, exemptions could be granted. This applied to men because there were few women who could even get a counter book, and servants were expected to sort under their master's quota.

On the more positive side for 1920 was that an eight-hour working day had just been introduced for the workers, and that was the last year only men had the right to vote. In the 1921 election, women would vote and be elected to the Riksdag for the first time in Sweden.

In a hundred years, the life expectancy had increased from 40 to almost 60 years. The infant mortality rate fell from 25 percent to 10 percent in 1920.

For the vast majority, life, for the most part, still consisted of hard work, but thanks to industrialization, most had still gotten it significantly better in 100 years.

Christmas 2021 – in your home

Since 1920, technological and scientific advances have been made at a pace unparalleled in history. It is easy to believe that development takes place with minor changes at a time, and above all, it takes place linearly. The reality is rather uneven and jerky.

Technological innovations suddenly throw us forward, and only after a while do we begin to understand how we can make full use of them. Electric candles in the Christmas tree have caused far fewer fires than their flammable counterparts, and with TV also came the Christmas calendar programs from 1960. During the 70s, meatballs became standard on the Christmas tables, and since 1988 we have found out what is this year's Christmas gift.

The Internet and smartphones have made information, communication, and influence available to billions of people. A working vaccine against Covid-19 took less than a year to develop. The computers continue to follow Moore's law and double their capacity while becoming smaller and cheaper every two years.

There is knowledge and capacity to make life better for everyone. Even though 2020 and 2021 go down in history as some of the worst years of our lives, it may also bring important and lasting lessons about what people can accomplish as we work hard and cooperate.

Today's life expectancy is over 80 years for men and almost 85 years for women in Sweden, which is twice as long as 200 years ago.

The infant mortality rate is 0.3 percent, a completely unparalleled success. Remember that the infant mortality rate was 26 percent two hundred years ago.

We in Sweden today have a standard of living that even the nobility could not dream of 200 years ago.

Of course, there are tiring jobs even today, but it is impossible to compare with how it was 100 and 200 years ago. Malnutrition is unusual, and today, everyone in Sweden has access to advanced healthcare. Very few have experienced the grief of losing a child.

And the best thing is that, despite a tough 2020 and 2021, the positive development is continuing.

🎅 From Warp News, we wish you a Merry Christmas – and look forward to an optimistic 2022.

By becoming a premium supporter, you help in the creation and sharing of fact-based optimistic news all over the world.